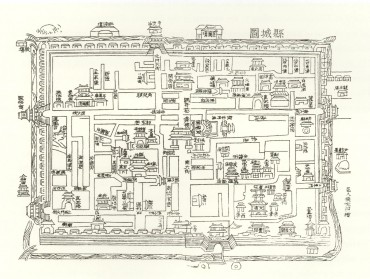

Sketch map of Pingyao in the record of Pingyao County in the 8th year of the reign of Quing Dynasty Emperor Guangxu

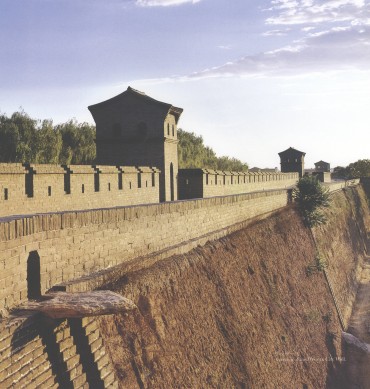

Section of the western wall

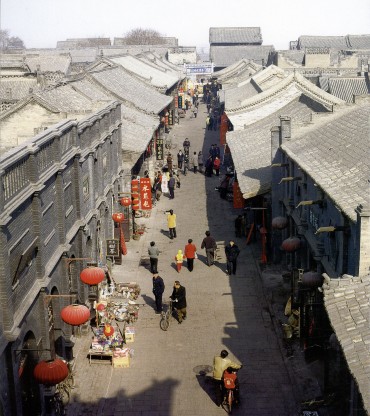

Lower Eastern city gate

Jar city

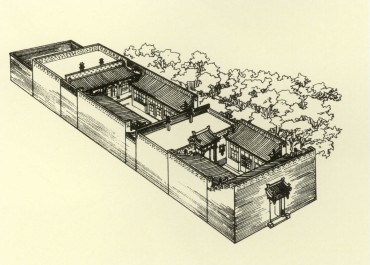

Portrait of a two-fold progressive courtyard

Courtyard houses

4.3.2013 – Issue 11 - Made In China – Obiol Cecilia – Essays

SUBJECTS AND OBJECTS

by Cecilia Obiol

The ancient city of Pingyao stands on the East bank of the middle reaches of the Fenhe river, which runs across the south of the Taiyuan Basin of Xanshi province. According to the Records on Pingyao County completed in 1882 the old city was established during Western Zhou Dynasty (827-782 BC), having a story of 2.800 years. The current city walls made by masonry and bricks were built in 1370 during Emperor Hongwu‘s period of the Ming Dynasty.

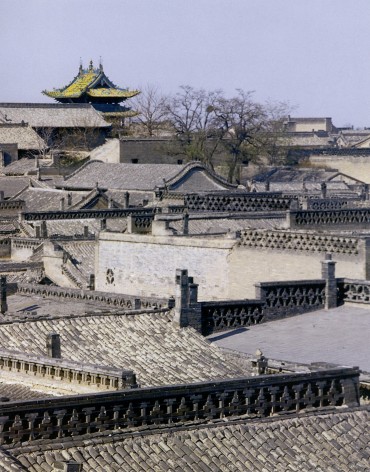

The plan of the city is a rectangle surrounded by walls. Inside the old city, occupying an area of 2.25 square kilometers, there are four avenues, eight streets and seventy-two alleys. The city walls are 10 meters high, 3-6 meters wide on the top and 9-12 meters wide on the bottom, and they were constructed with complete defense facilities including city towers, corner towers, ennemy towers and crenels. A total of 3.000 crenels are laid on the external side of the walls, and every 60-100 meters stands one of the 72 ennemy towers. There are six city walls -one on either side of south and north and two on either side of east and west. Outside every city gate there is another one called jar city, which is a small city surrounding the gate. The external gates of the city jars were closed when the ennemies came to attack, geting the troops enclosed like a turtle in a jar waiting for a sure catch, therefore the city got named as the Immortal Tortoise. The 3.000 crenels and 72 ennemy towers of the walls make reference to the historic tale of Confucius having 3.000 students and 72 virtuous people. Actually the whole city responds to the Confucian idea of ritual and propriety, benevolence and harmony, being an illustrative example of a Han Chinese city.

The well-preserved civil, military and religious buildings in the old city reveal the thriving past of the city, deriving from trade and later from the draft banks. However, the magnificent residential buildings are the clearer embodiments of the highness of local architectural level and the people‘s way of living. The most of them follow the styles and features of Ming and Quing periods and at the same time show strong local characteristics such as the strict and balanced arrangement based on the figures of square and cercle, the compacity of the spaces and the clear stress on fengshui, referring to location of the house being supposed to have an influence on the family fortune. They are built round four sides of an open courtyard, and are classified into three categories. The first are simple single-storey structures in wood and brick. The second are below-ground structures in brick with corridors lined with wood and extended eaves. The third are two-storey buildings, the underground brick structure being surmounted by a wooden second storey. In all categories the plan is generated by a two-fold or three-fold progressive courtyards.

The main principle of the architecture in Pingyao is the philosophical theory of man being an integral part of nature. Even if this approach is linked to the most old and traditional Chinese beliefs, even if the whole city of Pingyao is a picture of folk customs and cultural heritage, it is at the same time strongly connected to a very contemporary approach in the field of chinese architecture. Nor to the spectacularization of Beijing‘s urban development, neither to contemporary ‘starchitecture‘ carried out by foreigners to portrait the goals of China‘s transitional economy. Beyond these topical attributes a new generation of local architects is claiming for the construction of a present chinese identity by means of the background of local tradition. As Li Xiaodong states, we need to understand our own identity before we move forward. Few places in China could be more representative than Pingyao to illustrate the origins of such identity and the traditional architectural approach based in an overall conception in which buildings are breathing together with landscape.

As Tao Zhu explains in Building Big, with No Regret (AA Files 63, 2011), The search for China’s architectural identity was one component of the big efforts to forge a cohesive national polity and culture. During the period of the May Fourth movement in the 1910’s and 1920’s, the debate between the rival strands of radical anti-traditionalism and neo-traditionalism quickly found expression in China’s architectural development. Within the second camp, many architects pursued a National Style through ad hoc design experiments, while a group of architectural historians, led by Liang Sicheng, believed that an ‘authentic‘ Chinese style could be destilled through historical study.

Pritzker price winner Wang Shu is only a representative example of the new generation but there are many other chinese architects working in the same direction. Rather than looking towards the West they combine traditional understanding with an experimental approach. Their practice shows a big effort to create new environments, new atmospheres instead of producing mere objects to be contemplated. As Li Xiadong asserts Chinese never separate subjects from objects. This cosmological principle determines the course of new architectural practices in China where the buildings belong to the places and become an archive of human memories.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The ancient city of Pingyao, China Intercontinental Press, 2003. ISBN 7-5085-0250-7.

Ancient city of Pingyao, Unesco World Heritage Centre.

Building Big, with No Regret, Tao Zhu, AA Files 63, 2011.

Interview to Li Xiaodong by Anna Hotz, Cecilia Obiol and Huang Xusheng.

Download article as PDF