Selected Topic

Issue 9 - PREVI revisited – A Contemporary Approach to the Proyecto Experimental de Vivienda in Lima (June 2012)

Show articles

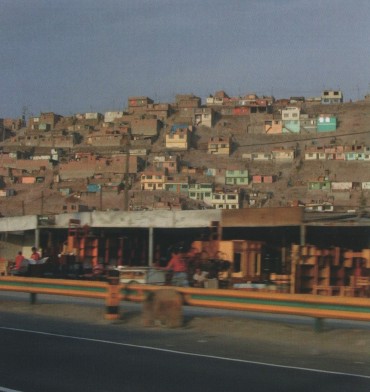

Informal settlement, Villa El Salvador, Lima (source: Time builds!, Ed.GG/ 2008, Barcelona)

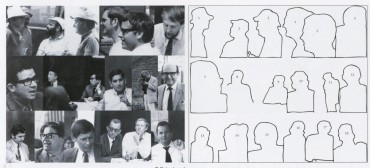

PREVI international architects, see note (1) (source: Time builds!, Ed.GG/ 2008, Barcelona)

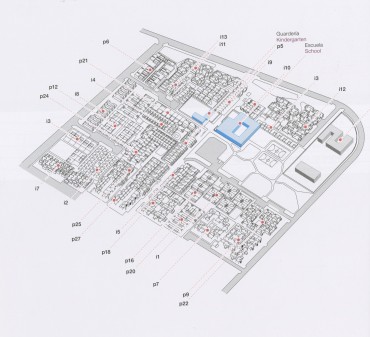

PREVI housing collage, see note (2) (source: Time builds!, Ed.GG/ 2008, Barcelona)

Frederick Cooper project in 1978(copyright: Peter Land)

Miro-Quesada-Williams-Nuñez project in 1978 and 2003 (source: Time builds!, Ed GG/ 2008, Barcelona))

Josic-Candillis-Woods project in 1978 and 2003 (source::Time builds!, Ed GG/ 2008, Barcelona)

4.7.2012 – Issue 9 - PREVI revisited – Cooper Frederick, Ramis Tomeu – Interviews

LOCAL BACKGROUND

Interview with Frederick Cooper

When the PREVI competition was announced in 1969, there was an intense debate in Europe in relation to the former CIAM approach to the city leaded by the young members of the Team10 and some of them were invited to participate in the competition. How did that debate influence the work of the young Peruvian offices that participate in the project?

I don’t think it exercised a direct influence. We were particularly aware of the sidelines of the debate because both myself and Antonio Graña had done post graduate work in the UK in the sixties. This experience brought us of course close to that debate, particularly in my case as I was a collaborator of the Architectural Design, a British journal that use to publish information on the growth of shanty towns and self-construction in Perú. Personally, I had developed throughout my student years a keen interest on the evolution of architectural ideas globally, and was thus well acquainted with the work of most of the architects that pertained to Team X. In fact, prior to PREVI we had done some work in the area of low cost housing for the Peruvian Government, where we tried to carry out the communal ideas locally.

One of the main issues of PREVI was to design an alternative to the massive informal settlements established in Peru during the second half of the 20th century. In that context, Which were the main principals to build up a community?

The question would require a protracted and difficult answer. To begin with, the settlements grew out of the intense immigration that began to flow into Lima around the middle of the century, mainly from the highlands. The people that poured into Lima came from rural communities, with lifestyles and resources totally alien to those of a large urban environment. This experience had occurred previously all along the nineteenth century within certain key European countries (The UK, France, Germany, Italy, Spain). Thus, the confrontation of this phenomenon ,locally should have considered that former experience, particularly because the incorporation of a rural population within an urban fabric was shown to have required a previous middle class assumption, so as to make known the inevitability of having to adopt housing and urban criteria of higher densities. This need was essential to secure the feasibility for the ulterior growth of a city into a metropolis, a process inevitably requiring higher densities for the sustainability of massive transportation, basic services and security. None of this was done, in spite of the fact that some of us insisted that the Peruvian Government should have had a more enlightened understanding of the implications of such a delicate and complex process.

The competition result was moved from the six original winners to the participation of 26 teams into a master plan defined by Peter Land . Comparing the final result to the original competition entries, do you believe that the variety of projects benefit the final result?

I believe the supposition that the projects could be carried out massively was mistaken in the brief, as it allowed for some of the proposals to consider industrial approaches that were not applicable, not to the completion requirements, nor to the country. Extending the number of competition entries to be built became a compromise that modified its initial purpose by transforming it into an elanrged sampling of individual housing and neighborhood environments, thus failing to confront the defiance of a massive growth in both aspects.

PREVI has been radically transformed by its inhabitants in programmatic and formal terms during the last 40 years. Your own proposal has experienced many changes .How do you consider the PREVI evolution in relation to your expectations of change through time?

Although we foresaw them, the fact that the project remained as an architectural sampling of low cost units, soon after abandoned by the Peruvian housing authorities led to wasting its important contributions to the development of a thoughtful and committed approach to the foreseeable consequences of a critical massive growth. The present conditions of urban life in the very extended suburbs of Lima is a sorry consequence of the interruption of the project.

After its completion, the PREVI crystallized, somehow, the changes in architectural and urban discourse during the late sixties, establishing a new route for future projects. Has it influenced other projects developed in Perú during the last decades?

I don’t entirely agree with the assumption that it was influential in the sixties. It certainly has not influenced other projects later, mainly because these were very scarce and mainly the outcome of political improvisation and outright social demagogy.

Which do you think is the most important contribution of PREVI to the architecture discipline? In other words, Why look again to PREVI after 40 years of its construction?

I think it offered a link between a serious social problem at its start, and the possibility of applying an illustrated professional approach to its prosecution. That possibility has still not been taken up. Thus, the spirit of the PREVI experience is still to be tried out seriously.

Interview by Tomeu Ramis

Note (1):

1-2.Jose luis Iniguez de Ozono, Antonio Vazquez de Castro. Spain/ 3.James Stirling. UK/ 4-5.Anatole du Fresne, Alfredo Pini. Switzerland/ 6.Toivo Korhonen. Finland/ 7.German Samper. Colombia/ 8/ 9.Fumihiko Maki, Kionori Kikutake. Japan/ 10.Charles Correa. India/ 11.Aldo van Eyck. The Netherlands/ 12.Peter Land. UN project director./ 13.Herbert Ohl. Germany./ 14.Knud Svenssons.Denmark/ 15.Christopher Alexander. USA/ 16-17.Oskar Hanson, Svein Hartloy. Poland/ 18.Alexis Josic (Candilis, Josic and Woods). France.

Note (2):

International participants: i1.James Stirling, i2.Knud Svenssons, i3.Esquerra-Samper-Saenz-Urdaneta, i4.Atelier 5, i5.Toivo Korhonen, i6.Herbert Ohl, i7.Charles Correa, i8.Kikutake-Maki-Kurokawa, i9.Iñiguez de Ozoño-Vazquez de Castro, i10.Hansen-Hatloy, i11.Aldo van Eyck, i12.Candillis-Josic-Woods, i13.Christopher Alexander.

Peruvian participants: p5.Miguel Alvariño, p6.Ernesto Paredes, p7.Miró-Quesada-Williams-Nuñez, p9.Gunther- Seminario, p12.Carlos Morales, p16.Juan Reiser, p18.Eduardo Orrego, p20.Vier-Zanelli, p21.Vella-Bentín-Quiñones-Takahashi, p22.Llanos-Mazzarri, p24.Cooper-Garcia-Bryce-Graña-Nicolini, p25.Chaparro-Ramírez,-Smirnoff-Wyszkowsky, p26.Crousse-Páez-Pérez León.

Download article as PDF